Hand-Dug Hope: Wells, Ditches, and the Homesteaders Who Watered the West

Irrigation and Ingenuity: How Abraham Todd, the Gerbers, and Early Settlers Made Granger Bloom

When early settlers like Joseph N Morris, Abraham Todd, John Gerber, and their neighbors first set eyes on the open flats west of the Jordan River in the 1870s, they saw promise: deep, rich soil and room enough to build a new farming community just nine miles from the Salt Lake Temple grounds. But they also saw an enormous challenge — in this arid desert land, water would make or break a homestead.

Abraham Todd, who came to Utah from England with his wife Ann Tofts Todd in 1866, knew farming well. He and other early homesteaders — men like Charles Barker, John Mackay, Henry Duncum, Jacob Hunter, Melvin Cook, and Edward Kendrick — broke ground in what would soon be called Granger, a name borrowed from an old English word for “farm house” and a nod to the Grange associations that supported frontier farmers.

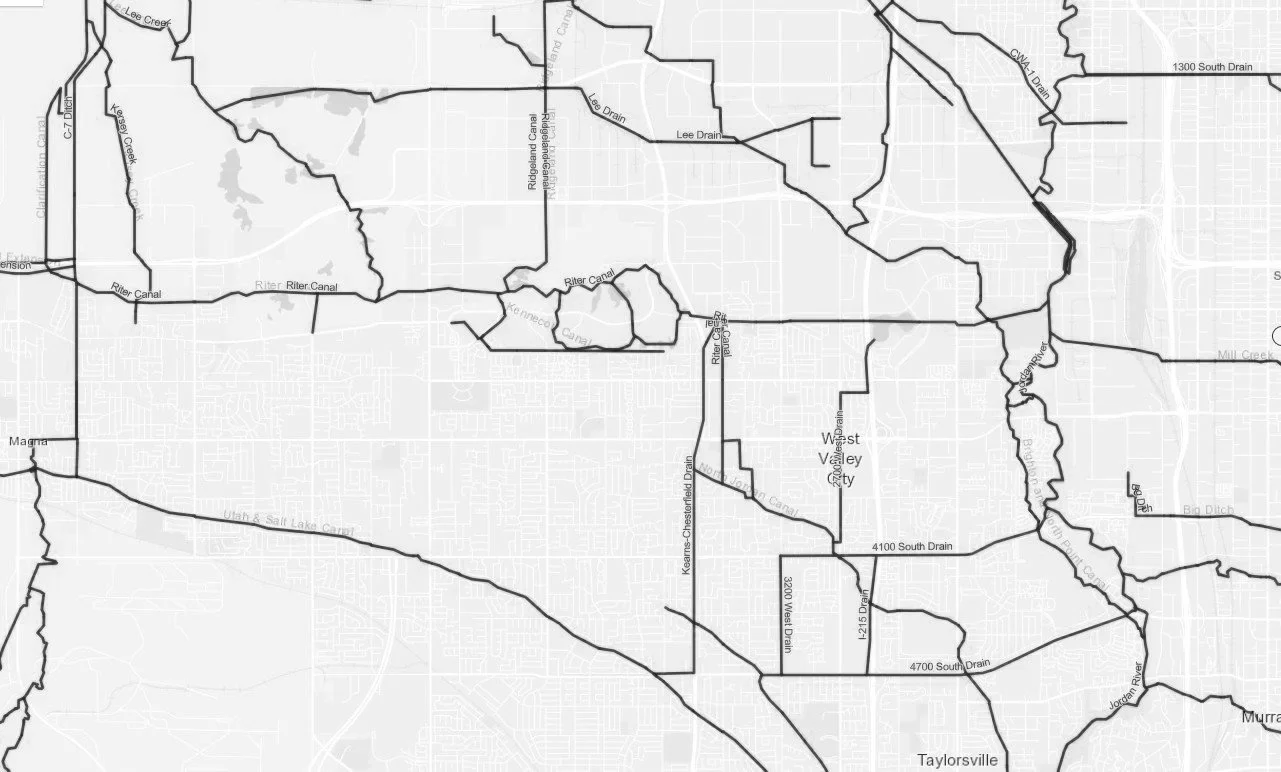

In those early years, crops came up thick and tall: wheat yielding sixty bushels an acre, corn so high the tops could barely be reached, and hay stacked deep for winter. Yet this prosperity couldn’t last without steady water. The first small ditches and “mill races” — like the Parker Ditch and Decker Ditch (later the Brighton Ditch) — brought precious irrigation from the Jordan River. But building canals was backbreaking work: hand-dug with shovels and horse teams, guided by little more than pickaxes and stubborn faith.

Abraham Todd and the Gerber family spent countless hours carving out these lifelines. They and other Granger families took turns digging, clearing brush, diverting streams, and repairing breaches after spring floods. Sometimes the new canals solved more than they spoiled — while they allowed more land to bloom, the settlers learned hard lessons too. In spots, the water left salt and minerals behind, which threatened to poison the soil. Yet with grit, the pioneers adapted: when water turned brackish, they pounded wells by hand — sometimes driving pipes 100 feet deep with nothing more than a sledgehammer and sheer muscle.

As water flowed, so did community life. Better irrigation made way for fruit orchards and leafy groves. William Barton’s sawmill turned local timber into beams and boards; Joseph Fairbourne’s blacksmith shop forged tools for wagon wheels and plows. The first schools sprang up in one-room buildings funded by tuition — a dollar or two a year. Miss Moore, the first teacher near the future Monroe School site, taught in a tiny chapel that doubled as a classroom.

Church and civic life grew beside the canals. On February 24, 1884, the Granger Ward was organized with just 150 settlers. Names like McRae, Sorenson, Bawden, and Mackay joined Todd and Gerber in building up farms, raising families, and planting trees. Locusts and fruit trees — thanks in part to George B. Wallace, the community’s own “Johnny Appleseed” — turned dusty flats into shady lanes and gardens.

Not all was peaceful — the community mourned when an acetylene gas tank exploded in the old meetinghouse in 1905, killing young Nellie Mackay mid-song and destroying the beloved chapel. But they rebuilt, just as they always rebuilt ditches, fences, barns, and faith.

Decades later, Granger’s canals remained a symbol of what grit and neighborly effort could do. What began as rough furrows carved by families like the Todds and Gerbers made thousands of acres green — a foundation that carried Granger from scattered farms to a thriving postwar suburb, complete with schools, stores, and water piped just about anywhere it’s needed.

Thanks to those first shovelfuls of dirt — and the hope behind them — Granger grew, prospered, and remembers.